Dementia and the Need for Control

Choice and Control are Powerful Forces in Dementia Care

August 04, 2021

I stood, waiting silently, as we faced the bathroom door side by side. She maneuvered herself ever so slightly, almost imperceptibly. After a few quiet moments she whispered, "now" and I slid the door open at her command.

We followed this ritual almost every time we left the bathroom. While many would argue there was no point to what she was doing, I would argue the opposite: it carried a tremendous amount of meaning and importance. It gave her the feeling of control.

After an impressive amount of success throughout her life, there was now little left she could control. Wracked with Parkinson’s, her body often ignored her intentions. Her neurons fired haphazardly, their messages rarely making it to their receptors. Whether or not she could swallow, stand, think or remember in any given moment felt random, and she certainly had no control over it.

So, if she could "control" when the bathroom door opened, it was absolutely worth valuing.

There’s no question that (up to a certain point) feeling in control over our own lives is helpful to our health. It’s true that when we try to micromanage every detail of our lives, and control the behaviors of others, we set ourselves up for distress and poor mental health. However, when looking at the other end of the spectrum – whether we believe that our actions and choices impact our lives or environment in a meaningful way, or that we’re helpless to affect our own life path – scientists widely acknowledge that people who feel generally in control over their lives tend to suffer less pain and anxiety than those who don’t.

People who believe they can influence their life situation tolerate the same painful procedures and anxiety-provoking events better than those who feel they’re at the mercy of the universe. They rate their levels of pain and distress significantly lower, and they experience fewer physiological signs of stress, like elevated heart rate and production of stress hormones.

Piles of evidence show that people who feel more control over their lives tend to enjoy better health in general, with fewer aches and pains. They tend to recover faster from surgeries and illness. They live longer.

Decades ago (when choice was less prominent in facilities than it is now), scientists studied the effect of giving older adults a little bit of control over their life. Half of the residents of one facility were granted special permission to choose which plant to grow in their bedroom, and to choose which movies to watch. This tiny amount of control was the only difference between the groups. Eighteen months later, they were twice as likely to still be living as the residents without choice.

Many scientists go beyond claims that having control is good for our well being, and argue that it is, in fact, essential for survival. It makes sense, biologically speaking. When our surroundings are safely under control, we have a much better chance to avoid ambushes or accidents.

This could explain why lack of control activates a fear response from the brain, and why humans naturally respond to a loss of control by actively trying to regain it.

Interestingly, cognitive scientists are finding that believing we have control over our environment – or at least having the sense that things are under control in general – is more important to our well being than actually having control.

That’s good news for those of us in dementia care.

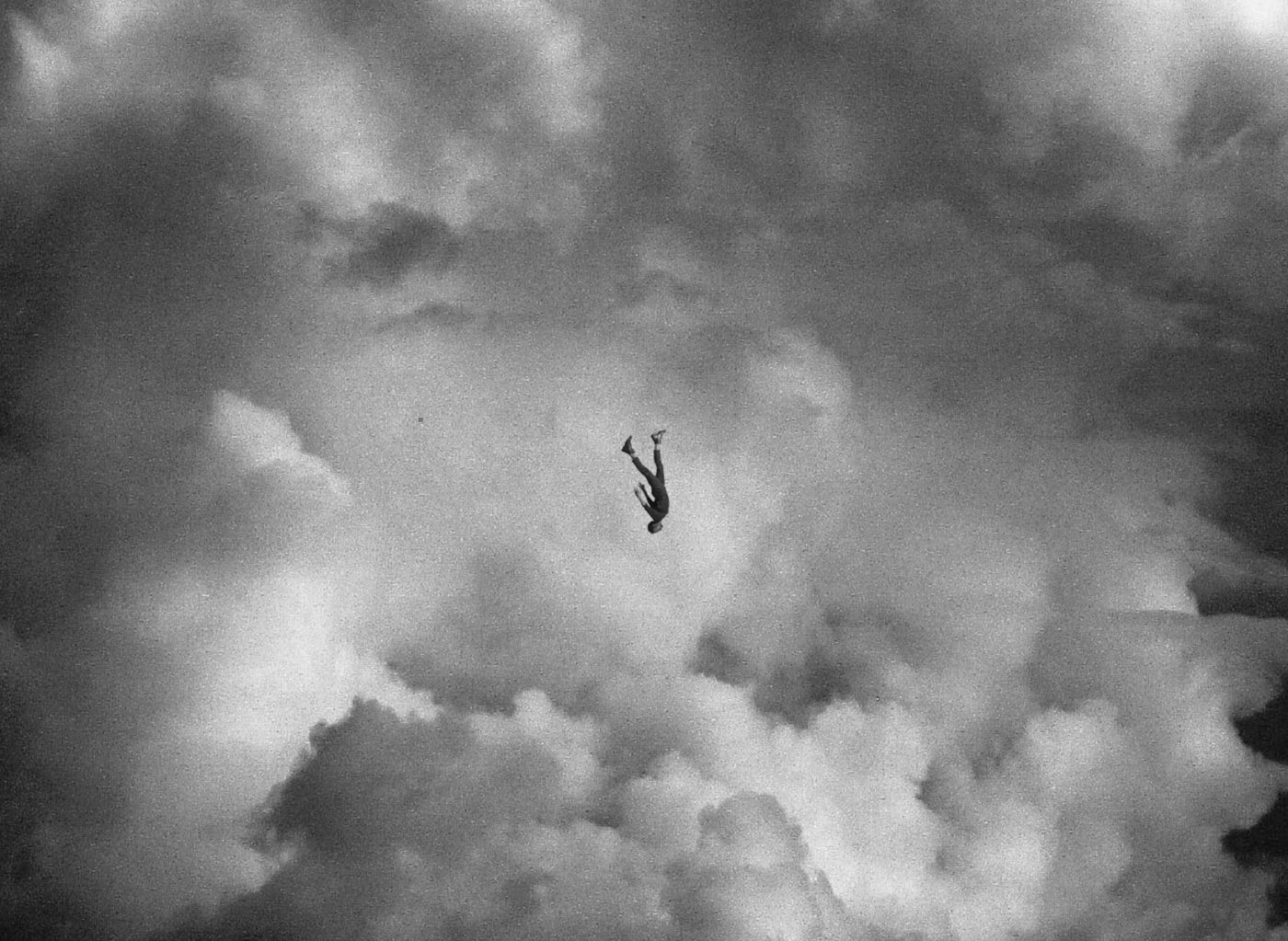

Fear, anxiety and insecurity erode our sense of control, and there’s little in life that rips our illusion of control out from under us more violently than a chronic terminal illness. Dementia, in particular, is incredibly hard on our ability to feel in control as it erases our memories, confuses our cognition and meddles with our minds.

When we feel our lives are careening out of control, humans have a natural tendency to fabricate the feeling. It helps calm our anxiety and bring about some peace of mind.

To create some semblance of control in our lives, we may:

- Insist on things being a certain way

- Reject others’ suggestions in favor of our own, without even considering them

- Create ritualistic (if perhaps seemingly pointless) patterns, like pacing along the same path repeatedly, touching the same spots each time.

- See patterns, find meaning or believe conspiracies where there is none

We like things to be in order, up to our standards and done the way we like them done.

Rituals provide predictability. We take comfort in everything being as it has been. It makes us feel more at ease.

When things are consistent we know what to expect. We feel safer and less vulnerable. (Consider how at ease you feel in your own safe, familiar situation versus a new environment with lots of unfamiliar people around).

It helps to know why something happened so we can choose to avoid (or repeat) it as needed

Imagine getting into the passenger seat in a vehicle. You’re comfortable that the driver will get you to the destination safely, so you relax for the ride. However, they suddenly start weaving erratically. You reflexively grab the wheel – an instinctual drive to regain control and survive.

Trust and control are intertwined. If we trust that someone will keep us safe we can relax. We can be that “someone” for our people with dementia. We can let them trust in us to keep them safe. How?

First of all, we need to be trustworthy all the time. We need to protect their trust in us. Regardless of how impaired they are, they will remember on some level when we break their trust.

We can do things the way they like them done. When possible, we can do them the same way every time, so they know what to expect. We can move slowly enough that they can process our actions and intentions without struggling to keep up. We can avoid triggering feelings of surprise, overwhelm or fight-freeze-or flight.

We can provide opportunities throughout the day for them to know the answer, be right and reach little goals. We can create opportunities for small achievements. Rather than always doing for them, we can help them be successful in doing what they want to do for themselves. We can help them see their successes, and we can avoid talking down to them or treating them like a child.

It’s important for them to feel they understand what’s happening – even if they actually don't. They may understand the situation partially, or even incorrectly. As long as they feel okay about it within their own reality, it’s good for their sense of control, and good for them.

Not only is feeling in control good for our health, but feeling we’re being controlled by others triggers all kinds of negative feelings deep within us. Anxiety, unease, frustration, annoyance or anger are common reactions when we feel like we’re being told what to do.

The term “reactance” describes the tendency to want to do the opposite of what we’re told to do. Reactance is a very common, natural reaction which is deeply ingrained in our human psyche. It’s why (dementia or not) we tend to feel uncomfortable, upset, angry or even aggressive when we get the sense we’re being bossed around.

Some people are more sensitive than others to the perceived threat of being controlled, and some people feel others are trying to control them, even when they aren’t.

A person with dementia may need our help, but we must take care not to come across as though we’re telling them what to do or trying to control them. When we do, we can easily trigger reactance “behaviors” such as resistance to care, irritability or aggression.

As beneficial as it can be to have some control in life, too many choices can be overwhelming. It causes a sensory overload that can trigger a fight, flight or freeze response. The result can be feelings of frustration, paralysis, inaction, fear or even aggression.

This is true for people both with and without dementia, although the person with dementia may have a much lower threshold for what they can handle, so it tends to be more obvious.

Most people with dementia find that two or three choices is usually plenty to wrap their minds around. Keep choices simple, remember to minimize words, and provide visual cues, if possible, to enhance understanding.

In rare cases, any amount of choice can be overwhelming and provoke anxiety. If the person often becomes distressed, even with simple choices, make decisions for them where needed – but don’t give up completely. Treading slowly and carefully, keep looking for areas where they may be comfortable making simple choices. Perhaps when they're feeling more rested or less stressed. Provide little clues to help buffer their confidence.

- "I know vanilla ice cream is usually your favorite! Are you in the mood for some today?"

- "Would you like your coffee with cream today, as usual?"

These clues help the person figure out their answer more easily and accurately, helping us boost their sense of competence, and allowing us to provide valuable opportunities for control without overwhelming them.

Provide plenty of small opportunities for the person with dementia to choose what they want, in ways that don’t overwhelm them. If needed, offer clues as to what their answer usually is, so they can answer with confidence and competence. Move slowly, doing things the way they want them done, in a predictable fashion.

Mrs. Rae never agrees to take a shower. So we no longer ask, but we can still meet her hygiene needs, while giving her a feeling of safety and control throughout the entire procedure.

She sits down on the toilet after supper. I have several clean washcloths, and a bottle of no-rinse soap at hand.

Me: Would you like a warm washcloth to wash your face?

Her: Yes, please

[I hand her the cloth and she takes some time to wash her face.]

Me: Would you like some lotion on your legs?

Her: Yes, please

[I ready a washcloth.]

Me: Let's start with this warm washcloth.

[I start to cleanse her legs slowly and methodically, working in the same order as always. I remove her pants, brief and socks and wash her feet.]

Me: Would you like clean socks tonight?

Her: Clean socks! Yes, please!

[I apply the lotion, a clean brief and clean socks.]

Me: Would you like a warm washcloth for your back?

Her: Yes, please!

[I lift the back of her blouse to cleanse her skin. I gently massage her back with the warm cloth.]

Me: Would you like to take off your blouse and I'll get your neck and shoulders?

Her: Yes, please!

[I slowly start to lift the blouse, attentive to whether she will take the lead in removing an arm from the sleeve. I let her do what she can, assisting only where needed. When the blouse is off I place a warm washcloth over her chronically painful neck and shoulder and let it sit a moment. I start to gently massage her shoulders with the warm cloth, working my way slowly down her arms and torso. After her torso is cleansed I hold up her favorite red nightgown and a blue one that she never chooses.]

Me: Which beautiful nightgown would you like tonight?

[She reaches for the red nightgown, as always, and I help her into it. After she’s dressed I hold out her electric toothbrush and a basin.]

Me: Your toothbrush is ready. Would you like me to turn it on for you?

[Usually she just takes the toothbrush, turning it on herself. Occasionally, she tells me to do it for her. After she’s brushed her teeth I ask if she’d like me to comb her hair.]

Her: Yes, please!

[I slowly comb through her hair, careful to allow the tines of the comb to gently massage her scalp. I look for signs that she needs a shampoo, such as skin flakes or greasy hair. If she doesn’t, I take a clean, warm washcloth and gently scrub and massage her hair and scalp. If a shampoo is in order, I do the same thing, with a tiny bit of shampoo on the cloth. There’s an extra step of rinsing the shampoo from her hair, using the same slow methodical movements with the warm cloth. I finish with another gentle combing through her hair.]

Me: How does that feel?

Her: Peaceful.

Me: Do you want more time on the toilet, or are you all finished?

Her: I’m all finished.

I cue her through standing up at the toilet, and finish the sponge bath with a warm washcloth to her upper thighs, buttocks and peri area.

She’s clean, calm and relaxed for the evening.

We stand, side by side, at the bathroom door. She maneuvers herself almost imperceptibly. After a few moments she whispers, "now" and I slide the door open at her command.

What have you noticed about how someone with dementia creates a sense of control for themselves? How have you helped them to achieve it?

Share your story on the ABC Dementia Facebook Page.

SHARE THIS PAGE!